Images of seven high-rise residential buildings engulfed in flames in Hong Kong in late November shocked the world. The fire, the city’s deadliest in decades, claiming at least 159 lives, is a devastating reminder of what can happen when governments suppress fundamental rights.

Authorities have arrested 21 people connected to a maintenance project at Wang Fuk Court, an apartment complex home to more than 4,600 residents. Preliminary investigations found that some of the netting covering the buildings did not meet fire safety standards.

There are widespread concerns that this is only the tip of the iceberg. Reports of substandard construction materials indicate a deeper rot: possible political corruption, bid-rigging and government negligence.

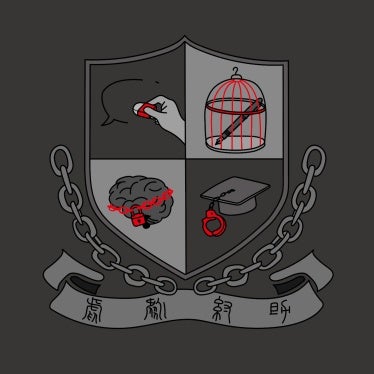

The tragedy also raises questions as to whether the fire could have been prevented if Hong Kong still had a free media, a thriving civil society, and a democratic legislature able to hold the powerful to account. Since 2020, when the Chinese government imposed a draconian National Security Law on Hong Kong, these safeguards on governmental abuse have been gutted.

Residents of Wang Fuk Court tried to warn of the dangers. They protested the hiring of a maintenance company with a poor compliance record and filed complaints with the government about safety issues, including their concerns about the flammable netting and workers smoking on site, but to no avail.

In the Hong Kong of the past, these warnings would have triggered media exposés and legislative hearings. Pro-democracy lawmakers—some with a track record of fighting against bid-rigging— would have ordered ministers to appear before the Legislative Council to answer tough questions. The popular newspaper Apple Daily would have splashed the story across its pages. Under the mounting pressure, officials responsible for building safety might have felt compelled to act. Instead, these lawmakers, journalists, activists, and Apple Daily founder Jimmy Lai are in prison, self-exile, or otherwise forced into silence.

Days after the fire, Hong Kong Chief Executive John Lee, who was hand-picked by Beijing, announced plans for an “independent committee” to investigate to an increasingly frustrated public. But when pressed for details about its powers, officials offered none, suggesting that the committee would be toothless.

The disaster reveals that the Hong Kong government feels no obligation toward the people of Hong Kong. Instead, it answers only to Beijing, and to Beijing’s overriding insistence on social control, which it masquerades as a matter “national security.”

Hong Kong authorities acted swiftly against those publicly critical of the government response and emerging grassroots efforts. Within a day after hundreds of Hong Kong people gathered donations and supplies for victims near Wang Fuk Court, Hong Kong police evicted the volunteers and government workers seized some of the aid.

Chinese and Hong Kong authorities accuse critics of “destabilizing Hong Kong.” National security police reportedly arrested a volunteer for “inciting hatred towards the government,” and a university student for starting an online petition demanding transparency and accountability. National security police forced a citizen-initiated news conference to cancel. Even Post-it condolence notes on public walls have been taken down. A public university covered up a student poster urging government action.

In many ways, the Hong Kong government’s responses resemble those of the Chinese government in similar situations. From the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake to the 2011 Wenzhou rail collision, to the 2020 Covid-19 outbreak, Chinese authorities reflexively censored information, muzzled dissent, and monopolized the narrative. The Chinese Communist Party makes it clear that only it can exert power: the power to determine what happened, who is to blame, and who gets help.

That hadn’t been the case in Hong Kong. Following the deadly Garley Building fire of 1996, Hong Kong’s then-British colonial government set up an independent commission of inquiry to investigate. The statutory body had sweeping legal power to compel and protect witnesses. A judge presided, and it led to major safety reforms.

When John Lee took office, he vowed to lead Hong Kong “out of chaos to order, and from order to prosperity.” Yet, by prioritizing control over rights, he failed the victims—and fails Hong Kong. Lee owes the victims’ compensation, and Hong Kong people an apology, an explanation, and – most crucially – accountability.

The Wang Fuk Court fire now seems like a brutal allegory: Hong Kong people are trapped in a system they did not agree to, and one that, sadly, they cannot escape.