Summary

The nightmare began the moment they took me off the plane.

—Gonzalo Y., a 26-year-old from Zulia State, Venezuela, July 31, 2025

The United States removed Gonzalo and 251 other Venezuelans to El Salvador in March and April 2025. When the plane landed, officers forced him and others to kneel with their heads down, he said. He told one of them that he had a spine problem and could not keep his head low, but one officer struck him with a baton in the back of the neck. On a bus to the maximum-security prison known as the Center for Terrorism Confinement (Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, CECOT), guards beat him again, he said.

“When we arrived at the entrance of CECOT, guards made us kneel so they could shave our heads,” Gonzalo said. “One of the officers hit me on the legs with a baton, and I fell to the ground on my knees.”

Everyone, he said, was subjected to the same treatment. “The prison director told us, ‘You have arrived in hell’. In CECOT, guards and riot police beat and abused the Venezuelans constantly. “The guards beat me many times, in the hallways of the prison module and in the punishment cell,” Gonzalo said. “They beat us almost every day.”

The Venezuelans were held incommunicado in the CECOT maximum-security prison for approximately four months, until July 18, when they were sent to Venezuela as part of a prisoner exchange between El Salvador and Venezuela.

This joint report by Human Rights Watch and Cristosal provides the most comprehensive account to date of the treatment these people endured during detention in El Salvador and includes the first detailed account of the treatment of detainees in CECOT. We interviewed 40 people who had been held in CECOT and another 150 people with credible knowledge of the experiences of the Venezuelans detained there, including relatives and lawyers. We reviewed a wide range of documents, including photographs of injuries, criminal records, and judicial documents in El Salvador and the United States, and also consulted international forensic experts.

The governments of the United States and El Salvador accused most of these people of being “terrorists,” part of Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan organized crime group that the United States has designated as a foreign terrorist organization. However, Human Rights Watch and Cristosal’s review of criminal record background documents indicates that many of them had not been convicted of any crimes by federal or state authorities in the United States, nor in Venezuela or other Latin America countries where they had lived.

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal found that the 252 Venezuelans were subjected to what amounts to arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance under international human rights law.

Gonzalo’s mother said her son called her on March 13, from immigration detention in the United States, to tell her he was going to be deported to Venezuela, where he would “give her the birthday hug he owed her.”

“I held on to that promise—but he did not arrive,” his mother said. As the days passed without information, she felt “unbearable pain.” The family called multiple detention centers, but US authorities denied information on his whereabouts. They only said he had been removed from the United States.

About a week later, a friend told Gonzalo’s mother that he had found Gonzalo’s name on a list published by a media outlet, naming the Venezuelans who had been sent to CECOT. She searched videos and photos of the deported men, hoping to recognize him, but she didn’t find him. “From that moment, everything went dark,” she said, “All I felt was anguish, pain, anger, and despair.”

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal found that the people held in CECOT were subjected to inhumane prison conditions, including prolonged incommunicado detention, inadequate food, denial of basic hygiene and sanitation, limited access to health care and medicine, and lack of recreational or educational activities, in violation of several provisions of the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, also known as the “Mandela Rules.”

We also documented that detainees were subjected to constant beatings and other forms of ill-treatment, including some cases of sexual violence. Many of these abuses constitute torture under international human rights law.

People held in CECOT said they were beaten from the moment they arrived in El Salvador and throughout their time in detention. Guards and riot police beat them in the hallways of the prison module and in a solitary confinement cell in a section of CECOT known as “the Island.” They beat them during daily cell searches for allegedly violating prison rules, such as speaking loudly with other detainees or showering at the wrong time, and sometimes for requesting medical treatment.

People held in CECOT said that many detainees were also beaten after US Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem’s visit in March, following visits by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in May and June, and after two prison protests occurring in April and May.

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal concluded that the cases of torture and ill-treatment of Venezuelans in CECOT were not isolated incidents by rogue guards or riot police, but rather systematic violations that took place repeatedly during their detention. Every former detainee interviewed reported being subjected to serious physical and psychological abuse on a near-daily basis, throughout their entire time in detention.

These beatings and other abuses appear to be part of a practice designed to subjugate, humiliate, and discipline detainees through the imposition of grave physical and psychological suffering. Officers also appear to have acted on the belief that their superiors either supported or tolerated their abusive acts.

Daniel B., for instance, described how officers beat him after he spoke with ICRC staff members during their visit to CECOT in May. He said guards took him to “the Island,” where they beat him with a baton. He said a blow made his nose bleed. “They kept hitting me, in the stomach, and when I tried to breathe, I started to choke on the blood. My cellmates shouted for help, saying they were killing us, but the officers said they just wanted to make us suffer,” he said.

Three people held in CECOT told Human Rights Watch and Cristosal that they were subjected to sexual violence. One of them said that guards took him to “the Island,” where they beat him. He said four guards sexually abused him and forced him to perform oral sex on one of them. “They played with their batons on my body.” People held in CECOT said sexual abuse affected more people, but victims were unlikely to speak about what they had suffered due to stigma.

The human rights violations documented in this report violate El Salvador’s obligations under international law, including the prohibitions on arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, and torture and other ill-treatment. US officials repeatedly denied relatives of people sent to CECOT information on their whereabouts, making the US government complicit in their enforced disappearances. The US government also violated its legal obligations to respect the principle of non-refoulement by transferring Venezuelan migrants to El Salvador despite easily foreseeable risks of torture and ill-treatment.

Many people who were held in CECOT said they continue to suffer lasting physical injuries and psychological trauma. “I’m on alert all the time because every time I heard the sound of keys and handcuffs, it meant they were coming to beat us,” one of them said.

The Venezuelans who were detained in CECOT have since been returned to their home country. Venezuela suffers a humanitarian crisis and systematic human rights violations carried out by the administration of Nicolás Maduro, which have compelled nearly 8 million people to flee. Some of the people held in CECOT had fled abuses by the Maduro government and its security forces and face the risk of persecution in Venezuela. Their repatriation to Venezuela violates the principle of non-refoulement. Additionally, in some cases, members of the Venezuelan intelligence services have appeared at the homes of people who were held in CECOT and forced them to record videos regarding their treatment in the United States.

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal call on the US government to end all transfer of third-country nationals to El Salvador. We also urge foreign governments and international human rights bodies, including the United Nations Human Rights Council, to substantially step up their public scrutiny of the US government’s human rights violations against migrants as well as El Salvador’s widespread human rights violations against detainees.

“We are not terrorists, we were migrants,” one of the people held in CECOT said. “We went to the United States to seek protection and the chance at a better future, but we ended up in a prison in a country we didn’t even know, treated worse than animals.”

Recommendations

To the US Government:

End any transfer or removal of third-country nationals and other people at risk of abuse to El Salvador, given prior reports of torture and ill-treatment in Salvadoran prisons and the evidence included in this report.

Stop the expulsion or involuntary transfer of noncitizens to third countries to which they have no genuine ties.

Disclose any agreements with El Salvador related to transfers or detention of US-transferred noncitizens.

Cease all funding to El Salvador’s police, army, prison system, and Attorney General’s Office until the government adopts verifiable steps to ensure accountability for and non-recurrence of the human rights violations documented in this report.

Issue an Executive Order rescinding the proclamation of March 14, 2025, which invoked the Alien Enemies Act to deport migrants to third countries.

Ensure that Venezuelan migrants who were deported to El Salvador under the Alien Enemies Act, and who are now in Venezuela, have a genuine opportunity to return to the United States, to continue with their asylum claims, should they wish to do so.

Refrain from removing people to countries where there are reasonable grounds to believe that they would be subject to torture and other serious abuses, as required under the principle of non-refoulement established among others in the United Nations Convention against Torture.

Respect the right under US law of any person who is physically present in the United States or who arrives in the United States, whether or not at a designated port of arrival, irrespective of the person’s status, to apply for asylum.

Take measures to ensure protection for Venezuelan migrants and asylum seekers. These include:

Respecting the legal status of people who arrived in the United States under humanitarian parole.

Respecting and extending the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) designation for Venezuelans, recognizing the ongoing conditions and risks that prevent many Venezuelans from returning to their country in safety.

Ensure that any financial, technical, or security assistance to El Salvador’s prison system, including CECOT, is conditioned on demonstrable improvements in detention conditions, treatment of detainees, and accountability for abuses, consistent with international human rights law.

To the Salvadoran Government:

Take urgent and effective measures to prevent torture and ill-treatment in detention facilities including by ensuring independent oversight, adequate training of personnel, accountability mechanisms, and access to legal counsel and medical care for detainees.

Conduct credible investigations into the abuses suffered by Venezuelan migrants transferred to CECOT from the United States—including beatings, sexual violence, forced nudity, and other forms of ill-treatment—and hold those responsible, including command-level officials, accountable.

Provide all detainees in CECOT and other detention facilities in the country with adequate food, safe drinking water, bedding, hygiene products, and access to natural light and ventilation, to prevent inhuman or degrading treatment.

Restrict the transfer of all detainees in CECOT and other detention facilities to solitary confinement to the maximum extent possible, ensuring its use remains exceptional, proportionate, and subject to strict oversight and judicial review.

Strictly limit the duration of confinement in solitary confinement, particularly for detainees with pre-existing health conditions.

- Ensure timely and adequate access to health care for all detainees in the country’s penitentiary system, including mental health services and uninterrupted provision of prescribed medications, consistent with international health standards.

- End the incommunicado detention regime of all detainees in El Salvador.

- Ensure that all detainees can exercise their right to legal counsel by facilitating confidential meetings with lawyers, providing adequate access to telephones, and guaranteeing timely information about their legal rights and ongoing proceedings during processing.

- Allow regular and unannounced access by independent oversight bodies—including the International Committee of the Red Cross, and relevant United Nations and Inter-American mechanisms—to all detention areas, including punishment cells. Ensure they can select interviewees and conduct confidential interviews.

- Guarantee strict non-retaliation protections for detainees who speak with humanitarian and human rights monitors, ensuring that all allegations of reprisals are promptly and independently investigated, and hold responsible officials accountable.

Create and maintain accurate, publicly accessible registries of all people detained in CECOT and other prisons, including dates of transfer, legal basis for detention, and contact with relatives, to prevent new enforced disappearances.

Reduce prison overcrowding at CECOT and in other detention facilities by ending unnecessary or prolonged pretrial detention and establishing an ad hoc review mechanism that 1) identifies cases involving higher-level gang leaders and perpetrators of violent crimes by gangs, including homicides, rape and sexual assault, disappearances, and child recruitment, which should be prioritized for investigations and prosecutions that respect due process and other fundamental rights; and 2) identifies cases of people who have been detained without adequate credible evidence, and whom authorities should promptly release. The mechanism should prioritize reviewing cases of children, people with disabilities, pregnant women, and people with serious health conditions.

To the Venezuelan Government:

Respect the rights of Venezuelan nationals returned from El Salvador, including by:

Ensuring they are not subjected to reprisals or stigmatization for having left Venezuela.

Immediately ending any surveillance and harassment by state authorities, including the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional, SEBIN), against returnees and their families.

Providing access to medical and psychosocial care, legal assistance, and the reissuance of identity documents.

To Other Governments, including Members of the Organization of American States (OAS) and European Countries:

Publicly and privately condemn human rights violations committed by the United States against migrants transferred to CECOT and urge the United States to end the transfer of third-country nationals to countries where they have no meaningful connections and the transfer of any migrant to places where they would likely be exposed to torture.

Publicly and privately condemn human rights violations in El Salvador’s prisons and urge El Salvador to conduct prompt, thorough, and impartial investigations into allegations of torture, ill-treatment, and other abuses at CECOT and other prisons, and ensure that those responsible, including command-level officials, are held accountable.

Cease all funding to El Salvador’s police, army, prison system, and Attorney General’s Office until the government adopts verifiable steps to ensure accountability for and non-recurrence of the human rights violations documented in this report.

To the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants, and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees:

Investigate allegations of ill-treatment, torture and other abuses in CECOT, as well as in other prisons in El Salvador, and report on them publicly, including to the UN Human Rights Council.

To the UN Committee Against Torture:

Investigate allegations of torture in CECOT and other prisons, and consider invoking the procedure established in article 20 of the Convention against Torture for countries where torture is “systematically practised.”

To the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights:

Publicly and privately condemn human rights violations committed by Salvadoran security forces at CECOT.

In the commission’s next annual report, consider including El Salvador in Chapter IV.B, which highlights country situations where there is a “systematic infringement of the independence of the judiciary,” where the “free exercise of the rights guaranteed in the American Declaration or the American Convention has been unlawfully suspended,” or where the “State has committed or is committing massive, serious and widespread violations of human rights,” among others.

Methodology

Between March 21 and September 2, 2025, Human Rights Watch conducted telephone interviews with 150 people, including relatives, friends, employers, and lawyers of detainees who provided credible information about the people sent to CECOT. These people were located in Venezuela, Colombia, and the United States.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 40 people who were held in CECOT following their release from prison on July 18.

Based on information provided by interviewees, Human Rights Watch and Cristosal documented 130 cases of Venezuelan migrants whom the Trump administration transferred to the CECOT prison. One hundred and twenty-five of them were sent to CECOT on March 15; four on March 30; and one on April 12. Cristosal provided legal assistance to the relatives of 76 Venezuelans held in CECOT, helping them file habeas corpus petitions before El Salvador’s Supreme Court.

Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish. Researchers explained the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews and how Human Rights Watch and Cristosal would use the information. All participants gave informed consent and understood they would not receive any form of compensation. Interviewees were informed they could end the interview at any time.

To protect interviewees from possible reprisals and given that several former detainees are pursuing legal action against the governments of the United States and El Salvador, Human Rights Watch and Cristosal have withheld their names and used pseudonyms. The report does not disclose identifying information unless explicit consent was provided and even then, only when doing so does not pose a risk to the individual. We have used pseudonyms even in some cases where interviewees had previously spoken to journalists and agreed to be publicly identified by their full names.

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal also analyzed documents provided by relatives and lawyers of detainees, including identity documents issued by the Venezuelan government, and in some cases, identity and social security documents issued in the United States. We also reviewed immigration documents issued by the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), asylum and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) applications, Safe Mobility program documentation, CBP One application records, as well as court filings and other legal documents submitted by detainees’ lawyers.

Human Rights Watch analyzed data on US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) deportations (“removals” by ICE’s definition) that ICE released in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request made by the UCLA Center for Immigration Law and Policy. Analysis in this report is based on the late July release made public by the Deportation Data Project. The data is supposed to include every deportation made by ICE. Crime data is the most serious charge that ICE has in its databases and is standardized according to National Crime Information Center (NCIC) codes. Analysis also uses arrests and detentions data released under the same FOIA request and linked to the deportation data by an anonymous identification variable.

Researchers also reviewed criminal background certificates from Venezuela, the United States, and other countries where the detainees had previously lived, including Colombia, Chile, Ecuador and Peru. We reviewed US state and federal court records.

We also reviewed sworn statements from some former detainees about the risks that led them to flee Venezuela, as well as statements from relatives, employers and others putting into question the US government’s claim that the detainees had any connection with Tren de Aragua.

In addition, Human Rights Watch and Cristosal consulted the ICE Online Detainee Locator System (ODLS) to review the status of several deportees and confirmed they had been removed from the system after their transfer to El Salvador. Researchers also examined records in the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) online database to corroborate information about immigration proceedings for most of the detainees.

Open-source research support was provided by students of the Investigations Lab of the Human Rights Center at the University of California, Berkeley.

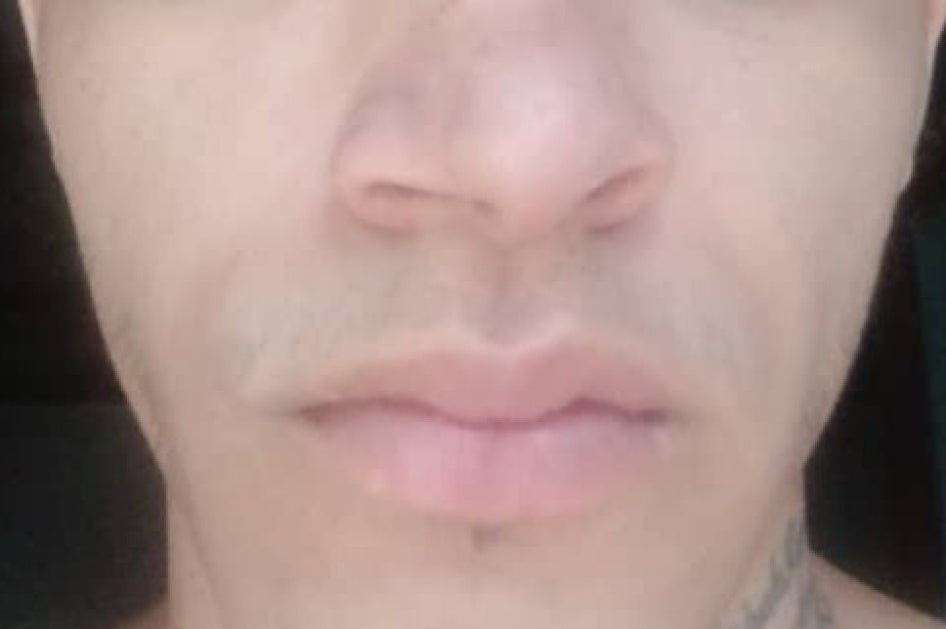

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal further analyzed photographs shared by some former detainees to corroborate their allegations about abuses suffered in CECOT. The Independent Forensic Expert Group (IFEG) of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT), an international body of prominent forensic experts, analyzed these photographs and confirmed that they are consistent with the detainees’ testimonies and their descriptions of the abuses they suffered.

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal maintained regular contact with international organizations and lawyers pursuing litigation before US and international courts, corroborating details and information related to the documented cases.

On September 18, 2025, Human Rights Watch sent letters to the governments of El Salvador and the United States summarizing our findings, posing questions, and offering an opportunity to comment on the research. At time of writing, Human Rights Watch had not received a response.

I. Background

On March 15, 2025, the US government removed 238 Venezuelan migrants from the United States to El Salvador, where they were immediately taken to the maximum-security facility known as the Center for Terrorism Confinement (Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, CECOT).

On March 17, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt announced that 101 of the Venezuelan migrants had been removed under Title 8 pursuant to regular immigration procedures, while 137 had been deported under the Alien Enemies Act.[1] This followed an executive order signed by President Donald Trump on March 14, declaring that Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan criminal group, constituted part of a “hybrid criminal state perpetrating an invasion of and predatory incursion into the United States.”[2]

In the 137 deportations carried out under the Alien Enemies Act, the administration claimed the Venezuelan migrants were members of Tren de Aragua and therefore a national security threat.[3] The Alien Enemies Act is incompatible with international human rights law and, as Human Rights Watch has argued in detail, the US Congress should repeal it. The Trump administration’s use of the Act to carry out the removals described in this report—and the subsequent abuses that those removals led to—offer an excellent illustration of the practical importance of that argument.[4]

Court records show that the Trump administration used a flawed checklist, that it called the “Alien Enemy Validation Guide,” to determine who qualified as an “alien enemy.”[5] The guide instructed US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers to assign points based on alleged indicators of Tren de Aragua membership, including tattoos, hand gestures, or clothing styles said to reflect allegiance to the group.

An expert on Tren de Aragua said in a sworn declaration that tattoos and hand gestures are not “reliable” or “credible” methods for identifying members of the group.[6] The expert emphasized that the government’s reliance on tattoos reflects “an incorrect conflation of gang practices in Central America and Venezuela,” and noted that Tren de Aragua does not have a distinctive style of dress.[7]

In the 101 cases where Venezuelans were removed to El Salvador pursuant to regular immigration procedures codified in Title 8 of the US Code, the administration provided no details about the circumstances of those removals.[8] Under Title 8, US authorities may remove individuals who enter the country without authorization, overstay or violate the terms of a visa, or are deemed inadmissible on criminal, security, or fraud-related grounds. People admitted legally may also be deported if they commit certain crimes or otherwise violate immigration laws.[9]

In most cases, removal under Title 8 involves detaining the person, issuing a Notice to Appear before an immigration judge, and holding a hearing in which the person can apply for asylum or other forms of protection. In some cases, however, expedited removal allows officials to deport people at the border without a hearing unless they express a fear of return, in which case they undergo a “credible fear interview.”

On March 30, US authorities carried out another flight, sending, among others, seven Venezuelan migrants to El Salvador, individuals they alleged were violent criminals tied to Tren de Aragua.[10] On April 12, another ten people, including at least one from Venezuela, were removed to El Salvador.[11]

The US—El Salvador Agreement

Neither the US nor El Salvador have fully disclosed the terms of the agreement under which the Venezuelan migrants were transferred to El Salvador.

However, the Salvadoran government has said that the US government paid them to hold these people in detention.[12] A US government grant letter filed in federal litigation shows that US$4.76 million was allocated through the US State Department to support Salvadoran security agencies. The letter indicates that the funds were intended to defray costs including those “associated with the detention of members of the Foreign Terrorist Organization Tren de Aragua (TdA), whom El Salvador has accepted from the United States.” It also indicates that El Salvador expressed its willingness to “accept and house approximately 300 members of TdA removed for up to one year or until another decision is made.”[13] In a Senate Appropriations Subcommittee hearing in May, Secretary of State Marco Rubio said that El Salvador had done the US “a big favor” and its government could “ha[d] a right to spend that money on any way they wish.”[14]

The agreement resulted in a significant increase in the number of third-country nationals sent to El Salvador.

The US and El Salvador have both claimed that the transferred Venezuelans were under the jurisdiction of the other. In response to a communication from the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, El Salvador asserted that it was holding the Venezuelans pursuant to an agreement by which the US retained “jurisdiction and legal responsibility” over them.[15] US Department of Justice attorneys, meanwhile, denied in federal court the existence of any agreement by which the US would retain “constructive custody” of the Venezuelans.[16]

Along with the 238 Venezuelans, on March 15, 2025, US authorities removed 23 Salvadorans, who appear to remain in detention. According to ICE data, over half had a criminal conviction (in some cases, for minor crimes), another 30 percent had pending criminal charges and 5, or 18 percent, had no criminal history. Their relatives told the press in October that, since their removal from the United States, they have been unable to communicate with them, or confirm their whereabouts.[17] On October 2, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights issued “precautionary measures” regarding the case of a Salvadoran national who appeared to have been removed to El Salvador on March 15 and whose whereabouts remained unknown. The Commission called on the Salvadoran state to take “immediate measures” to find him and report his whereabouts to his relatives.[18]

Among the Salvadorans removed on March 15 was César Humberto López Larios (“El Greñas”), top leader of the MS-13 gang, who had been arrested in 2024 and was awaiting trial in US federal court on terrorism-related charges.[19] A federal judge granted a request from prosecutors to dismiss the indictment against López Larios on March 11, enabling the US government to remove him to El Salvador.[20]

El Salvador’s ambassador in Washington, Milena Mayorga, acknowledged in an interview that President Bukele had asked US officials to return MS-13 leaders to El Salvador.[21] Internal correspondence cited in media reports indicates that Salvadoran officials discussed a “50 percent discount” on the fees for housing migrants in exchange for the transfer of nine high-ranking MS-13 members.[22] Federal prosecutors also asked the judge to dismiss an indictment against Vladimir Arévalo-Chávez, another high-ranking MS-13 leader, to enable his removal to El Salvador.[23]

The removal of López Larios may be part of an effort to ensure that MS-13 leaders do not testify in US courts about their alleged negotiations with the Bukele administration. According to indictments in US federal courts, MS-13’s top leadership in El Salvador negotiated with the Bukele government looser prison regimes, shorter sentences, early releases, and refusal to extradite leaders to the US. In return, they reportedly pledged to lower the homicide rate and provide political support during elections.[24]

Some gang leaders were released from prison as an apparent result of the negotiations with the Bukele government. For example, a prominent gang leader, Élmer Canales Rivera (“Crook”), was released from jail in El Salvador in November 2021 while serving a 40-year sentence. According to the Salvadoran news outlet El Faro, a senior Salvadoran official escorted him to Guatemala despite having an active US extradition request.[25] He was detained a year later in Mexico and extradited to the United States, where he faces charges first filed in 2020.[26] Similarly, Carlos Cartagena López, alias “Charli de IVU,” of the gang Barrio 18 Revolucionarios, said in an interview that authorities had released him from police custody in suspicious circumstances.[27]

The CECOT Maximum-Security Prison

The Center for Terrorism Confinement (Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, CECOT), a maximum-security prison in Tecoluca, San Vicente Department, was inaugurated on January 31, 2023, by President Bukele.[28]

According to the minister of justice and public security, the massive prison complex was built to hold “terrorist gang members captured by law enforcement.” It reportedly spans more than 236 acres and is completely isolated from any urban area.[29] It includes several facilities: housing modules, kennels for guard dogs, staff buildings, an armory, and a security equipment warehouse.[30]

CECOT is reportedly guarded by 600 members of the armed forces and 250 officers of the National Civil Police, who, according to the government, provide “24/7 security to address any possible disturbance.”[31] According to a 2023 BBC report, CECOT’s security staff also includes about 1,000 prison guards.[32]

According to open source research conducted by the University of California, Berkeley’s Investigation Lab, CECOT has eight modules with 32 cells each, totaling 256 cells.[33] Each module has at least six “punishment cells,” at least one medical room, and three rooms for virtual hearings.[34] Each cell contains four-level bunk beds with five cots per level, housing up to 80 prisoners per cell, which amounts to a total capacity of over 20,400 people.[35] Yet President Bukele has said that the prison can hold up to 40,000 detainees.[36] The Financial Times has estimated that if it held that number of detainees, each person would have 0.6 square meters of cell space.[37]

The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, also known as the “Mandela Rules,” recommend that the “number of prisoners in closed prisons should not be so large that the individualization of treatment is hindered.” CECOT’s design is inherently inconsistent with this international standard.[38]

The prison has no yards, recreational areas, or conjugal spaces. Each cell has only two non-private toilets and two water basins. There are no sinks, showers, natural light, fans, or ventilation systems. The aluminum bunks inside the cells lack mattresses and sheets and are designed to hold two prisoners per bed. Guards surveil prisoners constantly and the lights are always on.[39]

The prison holds “punishment cells” of 2.5 by 4 meters that contain a cement slab, a water tub with a bucket, basic drainage, and a toilet.[40] They are used to hold detainees in solitary confinement. Visits are not allowed.[41]

Prisoners in a “trust regime,” who under Salvadoran law are granted greater flexibility inside and are allowed to perform work, are tasked with distributing food to other detainees.[42] Meals are served in plastic containers and cups and passed through the cell bars. Detainees receive three identical meals a day.[43]

According to journalists who have visited CECOT, detainees eat with their hands, are allowed out into the central corridor of the modules for 30 minutes per day, and have their heads shaved every five days.[44]

The Venezuelans interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported that they were held in CECOT’s Module 8, which according to their testimonies consists of 32 cells arranged in two facing rows of 16, separated by a wide central corridor. They said that in the middle of the rows, there are at least six small punishment cells—known as “the Island”—each built for a single person, while directly opposite them is a room used as an infirmary. Several former detainees said that at the far end of the module, near the ceiling, there was a single window that provided the only source of natural light and air.

The University of California, Berkeley’s Investigation Lab found the former detainees’ descriptions to be consistent with publicly available videos and images of CECOT modules.[45]

Former detainees said each cell contained four large multi-level metal bunk structures placed in rows, without mattresses, pillows or bedding. There were two toilets in each corner and two sinks positioned near the entrance, just beyond the bars separating the cell from the corridor, along with two water tanks.[46] This description is consistent with photographs and videos of CECOT published on social media by the Salvadoran government and journalists, which the University of California, Berkeley’s Investigation Lab reviewed.[47]

According to open-source research conducted by the University of California, Berkeley’s Investigation Lab, three main security forces operate at CECOT: prison guards with the General Directorate of Prisons; officers with the National Civil Police’s riot-control units, known as the Order Maintenance Unit (Unidad de Mantenimiento del Orden, UMO); and members of the army.[48]

Berkeley’s Investigation Lab’s research indicates that the security forces’ armory in CECOT includes two types of military-pattern rifles and 12-gauge shotguns; only the shotguns can fire “less lethal” kinetic impact projectiles or lethal ammunition. The weapons are generally carried by guards on the second-level walkways. Riot control units are also deployed inside the modules wearing riot gear with shields, helmets, and protective masks. Members of the military appear stationed at external checkpoints and perimeter zones and are armed with military-pattern rifles.[49]

Several former detainees told Human Rights Watch that guards, both men and women, identified themselves by nicknames and kept their faces covered.[50] The nicknames included: Satán, Pantera, Felino, El Tigre, El Cuervo, Flecha, Vegeta, and Caín.

“The officers who guarded us in the module wore gray shirts and black pants. They always carried a baton, wore hoods, and had no identification,” said Marco P., a 25-year-old construction worker from Caracas.[51] “Few of them were without hoods.”[52]

“Among the guards, there was one called ‘Satan,’ who was the most abusive,” said Julián G. to Human Rights Watch.[53] “There was another known as ‘the Tiger,’ who was the boss of them all. And another, called ‘Vegeta,’ was the only guard who used a phone; he was the one who took photos and videos of us.”[54]

People held in CECOT said riot police regularly entered the module to support guards during searches and to help secure the cell block.[55]

Prior Reports of Torture and Abuse in El Salvador’s Prisons

The United States sent the 252 Venezuelans to CECOT despite credible prior reports that torture and other abuses were taking place in El Salvador’s prisons. This violates the principle of non-refoulement, established in the Convention against Torture, among others.[56]

Human Rights Watch, Cristosal, and other organizations have documented widespread human rights abuses and abusive prison conditions in El Salvador, including torture, ill-treatment, incommunicado detention, severe due process violations, and lack of access to adequate health care and food.[57] In 2023, the US State Department said in its annual report on human rights practices that El Salvador’s prisons “were harsh and life threatening due to gross overcrowding; inadequate sanitary conditions; insufficient food and water shortages; a lack of medical services in prison facilities; and physical attacks.”[58]

Additionally, a wide range of international human rights monitors have for years reported on the severe human rights abuses to which authorities subject detainees in El Salvador’s prisons, including torture, ill-treatment, lack of access to sufficient food, water and medicine, overcrowding, prolonged incommunicado detention, and failure to ensure protection from violence.[59]

Since the Legislative Assembly passed a state of emergency in 2022, which remains in place, Cristosal has found “systematic” abuses in El Salvador’s prisons, including the deliberate denial of food and drinking water, as well as physical and psychological torture.[60] Cristosal has reported that these abusive conditions have led to the deaths of at least 419 detainees since 2022.[61]

Until 2021, El Salvador’s prisons held just over 39,000 people.[62] Since the state of emergency, the prison population has surged to more than 109,000, making El Salvador reportedly the country with the highest incarceration rate in the world.[63] The government’s mass detentions have caused severe overcrowding and worsened prison conditions, including lack of access to drinking water and the spread of serious illnesses such as tuberculosis and skin infections.[64]

Cristosal has also documented that prison authorities have denied people in prison access to medication and timely medical care for serious or chronic illnesses, including those they had before entering prison and those acquired while in custody.[65] In some cases, prison staff refused to accept medication provided by family members. Authorities have also failed to provide medical care to detainees who were beaten while in custody.[66]

In addition to poor physical conditions, prison staff have committed repeated human rights violations. Upon arrival at prison, detainees are often subjected to abusive practices, including the excessive use of handcuffs and shackles, forced stress positions, beatings, and constant threats that they will not leave prison alive.[67]

Cristosal has also previously documented that prison staff routinely use physical punishment and torture, including kicking, punching, and the use of batons and pepper spray. Cristosal reports that these abuses occur in at least three contexts: during morning roll calls, inside cells as a form of intimidation or punishment, and in nighttime attacks targeting specific detainees.[68]

Cristosal has also reported that prison staff have combined physical abuse with humiliating and degrading treatment and have threatened detainees before and after visits by human rights and religious organizations. Authorities appear to use these tactics to prevent detainees from reporting the abuses and conditions they face.[69]

Cristosal has also previously documented the use of “punishment cells.” These are small rooms with no beds or regular access to sanitary facilities. Inmates held there are isolated for long periods of time, with limited access to water and food.[70]

CECOT, in particular, appears to have been built to violate the dignity and rights of the people held there, in violation of international human rights law and in contravention of standards like the Mandela Rules that articulate a rights-respecting vision of incarceration.

Statements by government officials indicate that the government intends to use CECOT as a place of permanent confinement. In February 2023, Justice and Public Security Minister Gustavo Villatoro said that those sent to CECOT would never leave alive. “As the Security Cabinet, we will make sure that the sentences are high enough so that none of those who enter CECOT ever walk out; they will only be able to leave in a coffin,” he stated.[71] That same month, Osiris Luna Meza, the head of the prison system said “All terrorists entering CECOT will never come out, and those sent to punishment cells will not see the light of day.”[72]

Detainees held in CECOT and other prisons in El Salvador have little to no access to justice. The Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court has yet to rule on more than 100 habeas corpus petitions filed by Cristosal on behalf of detainees; in some instances, the cases were filed more than three years ago. Despite multiple reports of torture and ill-treatment, Human Rights Watch and Cristosal are not aware of any charges against prison staff or members of security forces for abuses occurring in El Salvador’s prisons.

The US government has claimed in US courts that it has “ensured that aliens removed to CECOT in El Salvador will not be tortured, and [that] it would not have removed any alien to El Salvador for such detention if doing so would violate its obligations under the Convention Against Torture.”[73] The US government has declassified and publicly released a document where it seeks diplomatic assurances from the Salvadoran government that it would comply with the Convention Against Torture. The document notes that:

The United States understands that El Salvador will take these actions in accordance with its authorities under Salvadoran domestic law, and in a manner that is consistent with El Salvador’s international legal obligations regarding human rights and treatment of prisoners, including the Convention Against Torture.[74]

However, in the context of El Salvador, where torture is a serious and persistent problem, diplomatic assurances are not an adequate tool to prevent torture, and do not satisfy states’ obligations under the principle of non-refoulement.[75]

II. The Victims

On the basis of interviews with people held in CECOT, their relatives and lawyers, Human Rights Watch documented the different reasons that 130 of those held in CECOT originally left Venezuela, investigated whether they had criminal records in the United States, and researched their legal status in the US at the time of their transfer to El Salvador.

Reasons for Fleeing Venezuela

Venezuela faces three simultaneous crises: a crackdown on dissent, a humanitarian emergency, and a massive exodus of Venezuelans. Authorities persecute and criminally prosecute opponents, journalists, human rights defenders, and civil society organizations. With the knowledge of high-ranking officials, security forces and other government actors have been committing abuses that international experts are investigating as possible crimes against humanity.

Nearly 8 million people have fled the country since 2014 and over 14 million face severe humanitarian needs in the country, according to HumVenezuela, an independent coalition of civil society organizations in the country.[76] In 2024, around 86 percent of the population was living in poverty, with inadequate access to food, medicine, and other essential goods and services.[77]

Additionally, government authorities have persecuted, arbitrarily detained, and tortured members of the opposition, journalists, and human rights defenders, among others.[78] Since 2014, over 18,000 people have been subjected to politically motivated arrests, with over 800 political prisoners remaining behind bars as of September 2025, according to the pro-bono group Foro Penal.[79] Many have been subjected to enforced disappearances and incommunicado detention.[80]

The people held in CECOT and their relatives described the circumstances that forced them to flee Venezuela, often undertaking dangerous journeys across the Darién Gap and through dangerous areas of Mexico controlled by criminal groups.[81]

In at least 19 cases, people held in CECOT or their relatives said they fled Venezuela to escape threats, abuses, or persecution by state security forces, as well as threats posed by armed and criminal groups, including Tren de Aragua. Their allegations indicate that these individuals fled persecution and, in many instances, articulated strong claims for asylum.

- Pedro P., a 26-year-old man from Miranda State, Venezuela, said he joined peaceful protests against the government in 2018.[82] “We demanded an end to repression and called for lower prices on basic food products,” he said. Pedro said that the Bolivarian National Guard (Guardia Nacional Bolivariana, GNB) violently repressed the protest, firing rubber pellets and tear gas.

He said that a few days later the GNB summoned him for interrogation. A lieutenant threatened him with five years in prison if he joined other protests. About 15 days later, men carrying weapons, dressed in civilian clothes with their faces covered, entered the home of another protester he knew, he said. “They tortured him for hours with beatings and insults until he died,” he said. “We belonged to the same protest group, and all of us were threatened that we could suffer the same fate.”

Fearing for his life, he fled Venezuela in 2018 and after four years in Ecuador, he sought asylum in the United States. Mario J., a 32-year-old man, said that in 2023 he worked for a state-run television channel in Caracas.[83] He explained that he began to face “problems” when supervisors pressured him to share pro-government content from the channel on his social media accounts and he refused. “[Channel staff] accused me of being with the opposition because I refused and threatened to send me to prison. I was very afraid, and that is why I decided to leave and seek a new future in the United States.”

Julián G., a 29-year-old athlete who in 2020 began organizing fundraisers to support sports projects for children and youth in his municipality, said government officials accused him of receiving opposition funds and threatened to arrest him.[84] “I saw what was happening to other people who were accused of links to the opposition—they were threatened and persecuted. I didn’t want to go through the same thing, so I fled,” he said. He applied and was admitted to migrate to the United States through the Safe Mobility program in March 2024.[85]

Many others said they fled Venezuela due to the humanitarian crisis in the country, which impacted their capacity to obtain basic food or medicine.

- Rodrigo A., a 34-year-old man from Lara State, fled Venezuela in 2017 because he was unable to buy sufficient food, his mother said.[86] “There was so much scarcity here—we had no flour, rice, milk, or oil. In other words, there was no food,” she said. “My son had nothing to feed my grandchildren. They didn’t even have clothes; everything they wore was donated by neighbors or relatives.” She said her grandchildren eventually became ill from malnutrition. “They were very weak. At the hospital they told us to buy nutritional supplements, but we had no money, and the doctors didn’t have any to give us.”

She also became seriously ill. “I was diagnosed with cancer, and we had no money to buy my medicine, much less to pay for treatment,” she said. “All of this pushed my son to leave. He wanted to help us get out of poverty and, above all, to save his children from hunger and me from cancer.” - Flavio T., a 25-year-old man from Lara State, said that he fled Venezuela in 2017 because of the country’s economic collapse.[87] He worked as a driver but could not earn enough to buy food for himself and his family. He first traveled to Peru, where he continued working as a driver, but said he experienced severe xenophobia—people insulted him and called him a criminal because he was from Venezuela. In 2023, he decided to continue his journey north to the United States.

“We crossed through the Darién Gap,” he said. “The Gulf Clan stopped us and took our money to let us continue.” Flavio described continuing through Central America until reaching Mexico, where, he said, “the police would stop you, and if you didn’t pay, they sent you back.” On one occasion, he was returned to Guatemala before finally making his way back north.

Flavio reached the southern US border in January 2024 but was summarily sent back to Mexico, where he slept on the streets for several days. He then scheduled an appointment through the CBP One mobile application and presented himself at the US border in August 2024. - Sebastián Q., a 24-year-old man from Caracas, fled Venezuela in 2020 to send remittances to his family. “I thought from outside I could give my mother and children a better life,” he said.[88] Although he had multiple jobs in Venezuela, Sebastián said he could not earn enough in rural Bolívar State to feed his family.

He first moved to Peru, where he worked in fishing and construction. But he said he faced xenophobia, and even an instance of physical assault. “Just because you’re Venezuelan, they think you’re a criminal,” he said. He continued north toward the United States through the Darién Gap. In Mexico, he applied for a CBP One appointment and worked in construction, but after two months without a response, he decided to cross into the United States in July 2023. “Mexican migration agents shot at us when we ran before crossing the river. You had two options: cross or go back. If you crossed, they locked you up.”

Criminal Records

The Trump administration claimed that the majority of Venezuelans sent to CECOT were members of the Venezuelan organized crime group Tren de Aragua. Human Rights Watch and Cristosal found that in many of the documented cases, individuals had no criminal records in the United States, Venezuela, or other countries in Latin America.

Human Rights Watch analyzed data on US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) that ICE released in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request made by the UCLA Center for Immigration Law and Policy.[89] The data indicates that at least 48.8 percent of the Venezuelans deported to El Salvador on March 15, March 30, and April 12—the dates of flights Human Rights Watch confirmed transported Venezuelans to CECOT—had no criminal history in the United States.[90] Only 8 (3.1 percent) had been convicted of a violent or potentially violent offense.[91] The data only includes information on 226 of the 252 Venezuelan people who were held in CECOT.

ICE data also puts into question the Trump administration’s assertion that the removals were targeted against a specific group of highly violent foreign nationals. ICE data indicates that 13 percent of the Venezuelans sent to CECOT had prior criminal convictions, whereas 20 percent of the Venezuelans who remained in ICE detention, or were deported or released elsewhere, had prior convictions. Similarly, only 3.2 percent of the Venezuelans sent to CECOT had a violent or potentially violent conviction but 4.3 percent of the detained Venezuelans who were not had such a conviction. And a higher percentage of those sent to CECOT had no criminal history whatsoever (49 percent versus 43 percent).[92]

Human Rights Watch reviewed documents in 58 of the 130 documented cases of people held in CECOT, and all indicated that they did not have criminal records in Venezuela or other countries in Latin America.[93] Cristosal reached a similar conclusion on the basis of their review of criminal records and interviews with relatives of 76 people held in CECOT.[94]

Migration Situation

Many of the Venezuelans sent to CECOT appeared to have been denied the right to seek asylum in the United States. Out of the 130 cases Human Rights Watch documented:

- Sixty-two said they were removed while their asylum cases were pending. All 62 said they had passed their initial “credible fear interview” in the expedited removal process, which gave them the right to a full hearing on their asylum claims before an immigration judge, but their cases were all pending at the time of their removal to El Salvador.

- Four said that they were informed of their deportation orders while in detention, without being given the opportunity to challenge their removals.

- Sixteen sought asylum during deportation proceedings as a defense against removal and claimed they were denied a full process.

- Eighteen said they “voluntarily” agreed to depart due to a combination of poor conditions in migration detention centers and indications by ICE officials that they had no right to seek asylum.

- Three said they had arrived in the United States after completing a full vetting process and being processed through the Safe Mobility Offices program established by the US government and run by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). They said they had been conditionally recognized as refugees, but were detained at the airport apparently because CBP officers linked their tattoos to the Venezuelan organized crime group Tren de Aragua.

Additionally, ICE data indicates that 33 of the people ICE sent to CECOT had been previously held in ICE detention and released, including two people who had been detained and released twice prior to their deportation. Venezuelans who were sent to CECOT were previously released from ICE detention by being paroled, receiving humanitarian parole, released on their own recognizance or released on supervision.[95] The majority (19 out of 33) of the people that ICE had previously released had no criminal history and only 9 had a previous criminal conviction.[96]

III. Arbitrary Detention and Enforced Disappearances in CECOT

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal found that the US and Salvadoran governments refused to disclose information on detainees’ fates and whereabouts, and that their actions amounted to the crime of enforced disappearance under international law. Additionally, the detention of Venezuelan migrants in CECOT lacked a legal basis, making it arbitrary in violation of international human rights law.

Enforced Disappearance

Under international law, an enforced disappearance occurs when authorities, or those acting with their support or acquiescence, deprive a person of their liberty and then refuse to acknowledge the detention or disclose that person’s fate or whereabouts, placing them outside the protection of the law.[97] This practice also inflicts severe suffering on their relatives and loved ones.

The definition of enforced disappearance is set out in the 1992 United Nations Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.[98] El Salvador has ratified the 2006 International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance[99] and the 1994 Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons, which also prohibit enforced disappearances.[100]

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal found that the US and Salvadoran governments repeatedly refused to provide information on the whereabouts and fate of the detained Venezuelans.

The people held in CECOT were unable to communicate with their relatives and lawyers, and neither government published a list or else disclosed the names of the individuals sent to CECOT. CBS News, El Nacional and other outlets published lists of the people sent there, but the US and Salvadoran governments never confirmed their authenticity.[101]

All family members interviewed said that US immigration authorities initially told their relatives in immigration detention that they would be sent back to Venezuela. None of the detainees were told that they would be sent to El Salvador, the relatives said.

US authorities removed the people sent to El Salvador from ICE’s Online Detainee Locator System (ODLS). ICE indicates on its website that “the ODLS only has information for detained aliens who are currently in ICE custody or who were released from ICE custody within the last 60 days.”[102] According to their relatives, the names of the Venezuelans showed up in the system initially but then quickly disappeared, shortly after their transfer to El Salvador. This seems to indicate that the names were deleted sooner than is standard ICE practice. Most relatives and lawyers interviewed said they consulted the ODLS—the tool they had previously used to track the location of detainees during immigration proceedings—but consistently found “no results.” Human Rights Watch cross-checked the case numbers of several deportees in March and April and confirmed that they had been removed from the system.

US lawyers representing some of the people sent to CECOT said that immigration authorities never informed them of their clients’ transfers.[103]

Relatives of people removed said that when they called US detention centers or ICE offices to ask about their relatives’ whereabouts, officials told them that they could not provide any information, that their family members no longer appeared in the locator system, or that their whereabouts were unknown. In a few cases, officials informed them that their relatives had been removed from the United States, but did not say where they had been sent.

Some relatives said they emailed the then-Salvadoran presidential commissioner for human rights and freedom of expression, Andrés Guzmán Caballero, but received only an automatic acknowledgment of receipt or a response indicating that their request had been forwarded to the “relevant institutions.”[104]

Salvadoran courts refused to provide information on the whereabouts or fate of the Venezuelan people sent to the country. Between March and July, Cristosal assisted detainees’ relatives to file 76 habeas corpus petitions before the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court. The chamber has not issued a response.

Despite the lack of information from the US and Salvadoran governments, relatives, activists, journalists, and human rights organizations in the United States, Venezuela and El Salvador have identified many of those who were sent to CECOT. In many cases, relatives believed their loved ones were held in CECOT because they could not be found in immigration facilities in the United States and had been missing since the dates of the flights to CECOT. Their relatives were only able to confirm their whereabouts through leaked lists published by media outlets, information provided by the US government in later court cases, or upon the detainees’ return to Venezuela.

Selected Cases

ICE detained Tulio M., a 28-year-old man from Caracas, on March 13, outside of his apartment in Dallas, Texas.[105]

That night, family members began searching for Tulio, using ICE’s online locator system. When they entered his alien number, they first saw an alert that said “Call field office.” By the evening of March 14, the system showed that he was at Bluebonnet Detention Center in Anson, Texas, his brother said. His brother called the field office the next morning, on March 15, and was told that his brother had been transferred and was “in transit” to another facility. When he checked again later that day, the system indicated that his brother was in East Hidalgo Detention Center in La Villa, Texas. “I called that center, and they told me he was there awaiting deportation,” he said.

On March 17, the system still listed his brother at East Hidalgo, but when he called, an officer told him that his brother had been deported. The officer did not specify where and advised him to contact ICE. “I called ICE, but they told me he was still in Hidalgo and that I needed to wait 24 to 48 hours for the system to update,” his brother recalled.

By the morning of March 19, the locator system returned “zero results,” he said. From that day on, the ICE system provided no information. His brother was not included in the list of detainees CBS News published on March 20.

Tulio’s family called ICE multiple times but was repeatedly denied information.[106] On March 24, they received the first indication that he had been sent to El Salvador. Human Rights Watch reviewed a recording of the call, where an operator and a relative had the following exchange:[107]

Operator: The person you are trying to find is no longer in custody of ICE because he was removed to his country of origin, El Salvador.

Relative: What do you mean his country of origin, if he is from Venezuela?

Operator: Apologies, I did not mean to say country of origin, he was removed to El Salvador.

A month later, however, ICE operators continued to deny information on his whereabouts. In another phone call that took place on April 21, a relative and an operator had the following exchange:[108]

Operator: I see that he is no longer in the country, he was removed from the country.

Relative: To which country was he removed? Because he has not been sent to Venezuela.…

Operator: Here it only shows me the date, for that information I have to give you the phone number of the office that was in charge of his case so you can call.

Relative: That office number that you give me, I call and it goes directly to a voicemail, they don’t answer me because you have already given me that number on several occasions.

Operator: Then you have to send an email, sir.

(…)

Relative: How do you deport a person without giving them the right to a phone call, without letting them communicate with their family? Since Thursday, March 13, he has been deprived of liberty and he has never called.

Operator: Then call your consulate, sir, call the Venezuelan consulate to see what they advise you as well, but as I said … sir, here we cannot give you information, this is a call center, we only have some limited information.

Relative: … I am asking you if there is a complaints page or a claims page, because how is it possible that you go to ICE, who were the ones who took him, and they don’t give you information, not in the detention centers and not here either?

Operator: That’s why I tell you if you want to complain, complain to your Venezuelan embassy and you can give that information to them….

Venezuela has had no functioning embassy or consulates in the United States since 2023.[109]

Soraya G., the 23-year-old wife of a Venezuelan migrant detained in the United States, told Human Rights Watch that after losing contact with her husband on March 14, she checked the ICE locator system using his alien number—the same one she used to send him money so he could call her—but found no result.[110] “They had taken him out of the system,” she said. “I tried to call ICE, but nobody answered. I spent the night without sleep from the anguish.”

For several days, she could not find any trace of him in the system or through ICE hotlines. Soraya said she only learned that he was in El Salvador about five days later, when she saw his name on a list published by CBS News. “I called ICE again…. An officer told me that he had been deported. I asked where to, and he told me he couldn’t say.” She recalled asking the reason for his deportation, since her husband had entered through the CBP One appointment system and was in the middle of his asylum process. “The officer told me he had been deported because he had entered illegally.”

Carmenza J., a 47-year-old mother of one of the Venezuelans detained by ICE, said that the last time she spoke with her son was on March 15.[111] “Mom, see you at home. ICE told me they are sending us to Venezuela today,” she recalled he said.

After that call, she lost contact with him. “On March 16, I asked several people in Caracas if flights from the United States had arrived, and they told me no. I checked the ICE [locator] system and it showed zero results and they didn’t answer the phone,” she said.

She asked a relative in the United States to call ICE. “They answered him once and told him they couldn’t give any information. They just said not to call again because my son was no longer in the United States,” she recounted. “That was horrible for me and my family, especially for my grandson, because we thought he had disappeared. My grandson asked about his father every day, and I didn’t know what to tell him.” Carmenza said she called ICE daily, but no one ever answered.

Abigail R., a 38-year-old sister of one of the Venezuelans held in CECOT, said that the last time she spoke with her brother was on March 15.[112] “He called me at 8 a.m. to say they [ICE officials] were going to deport him to Venezuela. That was the last time I spoke with him,” she recalled.

After borrowing money from a neighbor, she traveled by bus to Caracas to wait for him. At the Maiquetía airport, she joined relatives of other detainees, but as night fell and no flight arrived, she searched for her brother in the ICE locator system and found “zero results.” “That’s when I realized something strange was happening because before he appeared at the detention center in El Valle [in Texas] … that same day they [ICE officials] removed him from the system,” she said. She tried calling ICE but received no response. “I kept calling for the next five days. On the fifth day, an officer answered and told me, ‘He was deported, he’s outside the United States, I can’t tell you where,’ and then she hung up,” Abigail said. “I called again, crying in desperation, and the same officer answered and told me, ‘Don’t insist, they’re no longer here, find a lawyer to help you.’”

Detention Without a Legal Basis

Under international human rights law, any deprivation of freedom must, among other requirements, have a basis in law. Arbitrary detention is prohibited.[113]

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal have been unable to identify any actual or even purported legal basis for the detention of Venezuelan migrants in CECOT. On April 5, Human Rights Watch sent a letter to El Salvador’s minister of justice and public security and to the then-presidential commissioner for human rights and freedom of expression requesting information on the identity of those detained, their conditions of detention in CECOT, and the legal basis for their detention.[114] On April 25, the presidential commissioner for human rights and freedom of expression replied, stating that his office did not have the requested information. The minister of justice and public security did not respond.[115]

In March and April, Cristosal formally requested access to public information from several Salvadoran government institutions—including the General Directorate of Prisons, the Office of the Human Rights Ombudsperson, the Presidency, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs—seeking the official list of Venezuelans deported from the United States to Salvadoran prisons, as well as a copy of the agreement between the two governments authorizing these transfers.

In late March, the General Directorate of Prisons responded denying access to the information and declaring the list of those affected by this measure confidential for seven years.[116] To date, no Salvadoran state institution has officially released a complete list of individuals detained in CECOT as part of this agreement with the United States.

Additionally, on September 18, Human Rights Watch sent letters to El Salvador’s minister of justice and public security and foreign minister requesting information on the legal basis for the detention of people in CECOT.[117] They had not responded at time of writing.

On April 11, Human Rights Watch issued a press release calling on the government of El Salvador to “disclose whether there is any legal basis” for these persons’ detention.[118] Yet to Human Rights Watch’s and Cristosal’s knowledge, Salvadoran authorities have not made any efforts to point to any possible legal basis.

In response to a communication from the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, the government of El Salvador denied that its authorities had “detained” these people, indicating that they had rather “facilitated the use of the Salvadoran prison infrastructure for the custody of persons detained within the scope of the justice system and law enforcement of that other State,” meaning, the United States. The government of El Salvador did not cite a basis for their detention.[119]

In May 2025, Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights, the Boston University School of Law International Human Rights Clinic, the Center for Gender & Refugee Studies, and the Global Strategic Litigation Council filed a request for precautionary measures before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, urging the commission to order the immediate release of hundreds of people detained in CECOT.[120] The organizations said El Salvador asked the commission to dismiss the case following the return of the Venezuelan migrants to Venezuela.[121] The commission has yet to issue a decision.

IV. Torture, Sexual Violence, and Other Forms of Ill-Treatment in CECOT

The [CECOT] director told us, “You have arrived in hell. Here you will spend the rest of your lives.”

—Juan R., a 39-year-old businessman from Caracas, Venezuela, July 31, 2025[122]

All the people detained in CECOT that Human Rights Watch and Cristosal interviewed said prison guards and riot police subjected them to regular physical, verbal, and psychological abuse from the moment they arrived in the country. These abuses amounted to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment and, in many cases, torture under international human rights law.

Former detainees recounted the abuses they suffered and corroborated accounts by other interviewees, including those who were their cellmates or were held in adjacent cells within their line of sight. This allowed Human Rights Watch researchers to cross-reference allegations and incident accounts. Additionally, whenever possible, Human Rights Watch obtained photos of the injuries suffered by the detainees and solicited expert opinions from the Independent Forensic Expert Group (IFEG) of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT).

Human Rights Watch and Cristosal concluded that the cases of torture and ill-treatment of Venezuelans in CECOT were not isolated incidents by rogue guards or riot police, but rather systematic violations that took place repeatedly throughout the Venezuelan migrants’ detention. In fact, this conclusion is inescapable. All the former detainees interviewed reported being subjected to serious physical and psychological abuse on a virtually daily basis and throughout their entire detention.

The beatings and other abuses appear to be part of a practice designed to subjugate, humiliate, and discipline detainees through the imposition of grave physical and psychological suffering. The brutality and repeated nature of the abuses also appear to indicate that guards and riot police acted on the belief that their superiors either supported or, at the very least, tolerated their abusive acts.

According to the people held in CECOT, the most severe beatings and abuses took place on the way to or inside the punishment cells known as “the Island.” Guards took detainees there to punish or intimidate them, often under the pretext that they had violated prison rules.

Former detainees described the punishment cells as small, dark spaces that can fit only a few people standing. They said these cells were approximately 3 by 4 meters and contained a cement bed, a toilet, and a sink area, with a hole in the ceiling that sometimes allowed in light and air.[123] Several interviewees said they were sometimes taken there alone, and at other times in groups of up to 8 to 10 detainees all held in the same cell.

After beating and otherwise abusing detainees, guards left them locked in punishment cells, for periods ranging from four hours to three days, during which they were assaulted multiple times. Several interviewees said that guards restricted their access to food, water and medicine during their confinement.

In addition to the periodic beatings, several former detainees told Human Rights Watch that guards subjected them to other forms of ill-treatment. They said guards tightened their handcuffs excessively or stepped on them while they were in what guards called “search position”—handcuffed and shackled, forced to kneel with their hands behind their heads—, sprayed pepper spray at them without any provocation, shouted at them constantly, accused them of being criminals, and used degrading language. Others said guards threatened them and their relatives, telling them they would never leave alive, that they had been sentenced to 100 to 200 years in prison, and that they would never see their families again.

Beatings

Former detainees said they were subject to periodic beatings when guards conducted searches of their cells, when they considered that detainees had broken the prison’s rules, and in some cases when they requested medical attention. They also described when the beatings and torture they suffered occurred, and identified times throughout their detention, including:

- Upon arrival in El Salvador and as they were transferred to CECOT

- Following the visit of US Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem

- Following visits by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in early May and mid-June

- Following two protests by detainees that took place in April and May

Beatings Upon Arrival in El Salvador and Transfer to CECOT

All of the former detainees Human Rights Watch and Cristosal interviewed said that physical abuse began as soon as the planes landed in El Salvador.

Riot police forced them off the aircraft, in most cases punching them in the stomach at the door. Officers then forced the detainees to descend the stairs shackled at the wrists, ankles, and waist, with their heads lowered, and beat them again as they made their way down. The beatings continued—with fists, kicks, and batons—as the detainees were herded onto buses that transported them to CECOT.

Once inside CECOT, guards took the detainees to an area where, they said, other prisoners in yellow uniforms, acting under guards’ orders, shaved their heads. Guards then forced them to strip, put on a prison uniform, and shackled them by their wrists and ankles before loading them onto another bus to Module 8, where the beatings continued. According to their testimonies, just meters before the entrance, riot police and guards forced the new arrivals to run a gauntlet of prison guards, who beat them with batons, fists, and kicks as they entered. Former detainees said those who fell were forced back on their feet and beaten more severely.

Julián G. was taken off the plane in El Salvador by a riot police officer who hit him several times in the ribs with the butt of his rifle.[124] Between the plane and the bus, he struck him several more times in the back of the neck and back. Once he arrived at the entrance of CECOT, he said an officer hit him and pulled him off the bus. “He punched me in the ribs so hard that I couldn’t breathe. Then they took me inside, made me kneel, and shaved my head.”

On the bus to Module 8, Julián said, guards joked among themselves, saying, “Bukele really loves us, he sent us more than 150 gang members to torture.” He said he could not walk well because his left foot was injured, and he began hopping on his right foot as he left bus. But guards beat him more. “At one point, my right leg gave out, I fell, and a guard grabbed me by the chains on my handcuffs and shackles and caused me intense pain.”

When he walked into Module 8, Julián said he heard screams from beatings and saw traces of blood on the floor, and a man convulsing.

He said that when they arrived at the prison, CECOT’s director told the detainees “Welcome to my prison…. You are here as convicts…. The only way out of here [is] in a black bag.”Silvio T., a 23-year-old man from Caracas, said that as soon as he was called off the plane, a hooded unidentified officer punched him in the stomach, handcuffed his hands and feet, and pushed him down the stairs toward a bus.[125] When he and others got off the bus at the CECOT entrance, officers made them crouch down and run handcuffed. Silvio said he shouted to officers that he couldn’t keep running because he was asthmatic and was going to faint. When he fell to the ground, an officer kicked him in the chest and said “Here, we beat those who faint even harder.” He pushed Silvio and forced him and others to kneel on the floor as officers punched them in the backs of their necks, calling them “fucking gang members,” and ordering them to take off all their clothes.